Memories of Battle & Boredom

- Ahmed

- Mar 29, 2019

- 4 min read

Updated: May 6, 2024

The First World War is the source of many collectibles and antiques but Trench Art is one of the oddest and perhaps most moving.

Today I'll write about some pieces we have in the store which we could classify as 'Trench Art'. A broad definition would be art made by combatant and non combatants in the midst of wartime. It has social relevance as it tells us a lot about the conflict as well as the artist him/herself. The 1914-18 war was unusual for lots of reasons. One which interests me is a social aspect which shows us how much the world has changed: it was also the type of men involved. Most were working class, in the sense they were used to physical labour with their hands and bodies. All would have some level of artisanal ability, be it carving, whittling or working with metal. This is a theme which I bring up here quite often, the ability to work with your hands to fix and make, as something we've sadly lost.

This is linked to where the men came from. By 1914 the UK and Germany were already very urban societies. France on the other hand was still profoundly rural. Soldiers came from across the countryside, and a visit today to even the smallest hamlet will show this in its war memorial. The French army of 1914 was one of village men, farmers and workers from small towns. The announcement of hostilities and the general mobilisation was in August at the beginning of the harvest. Men would put down their pitchforks to collect rifles. Of course it was the women who would the pitchforks pick up again.

(Via France 3)

The ultimate loss of nearly 1.7m people- 300,000 civilians- would have an impact on the French population that would later affect events in 1940... but that's another story. It was the first really mechanized industrial war in Europe. This results in tanks and machine guns but also, given the consequence of battle, vast amounts of detritus. Metal and wood shrapnel as well as helmets, cartridge shells lay strewn across battlefields and barracks.

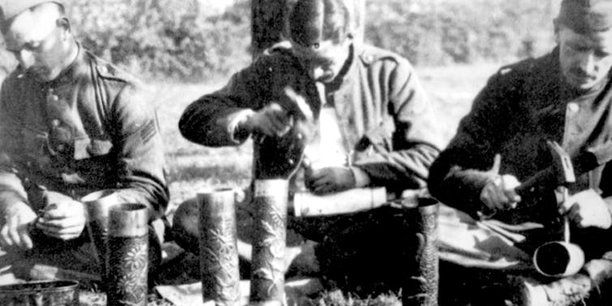

Trench warfare was a long drawn out affair with soldiers rotating between rest periods behind the front or at barracks punctuated by short intense periods of extreme violence at the front. Large numbers of men, all capable of handicrafts with access to huge amounts of scrap material. It should be unsurprising to find soldiers didn't try to find ways to keep occupied and also psychologically recuperate. The result is "trench art", small hand made objects, usually fashioned from shrapnel or debris by soldiers.

(Belgian soldiers decorating possessions via La Tribune)

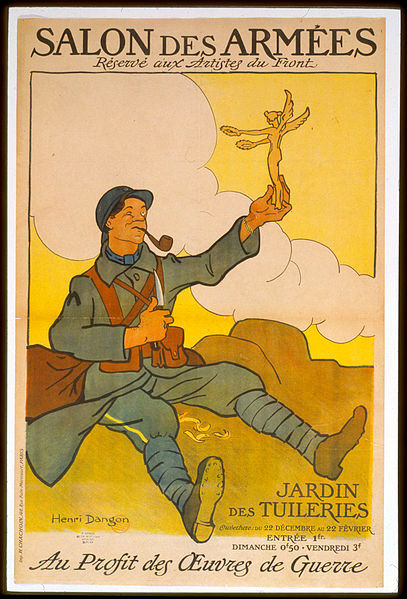

It became so well known that popular French magazine Le Pays de France sponsored a series of competitions for the best art pieces created by French soldiers. The magazine called these objects l’artisanat des tranchées. Soldiers would send these home to loved ones or even trade them with other soldiers. The military authorities themselves also participated by holding exhibitions, recognizing the propaganda value. One of these exhibitions, entitled "The Art of War", ran from December 1915 to February 1916 in the halls of the Jeu de Paume at the Tuileries in Paris. It brought together nearly 2,800 works.

After the Americans entered the war in 1917, the enthusiastic volunteers who arrived in France became voracious collectors of war souvenirs sold by French soldiers and by the shops behind the front lines that offered decorated shell casings, cigarette lighters, and other examples of trench art. The quality of some of these pieces is extraordinary and there is still a lively market for them.

(via The Magazine)

Similarly, vast numbers of men were taken prisoner and found themselves bored and far from home. Many POWs would make small items that they could trade with each other or send home. "Internees from the British First Royal Naval Brigade held in Groningen, in the neutral Netherlands, for example, created wooden souvenir picture frames and boxes that were sold at major department stores in London" (quoted here) Of course, POWs could turn their hand to anything that required time and energy, even embroidery:

(Via here more here) It may seem an odd thing to want to remember, but bear in mind there were several hundred thousand men kept as POW in camps across Europe. In fact over 500,000 Frenchmen had been held prisoner in any of over 300 camps across Germany and occupied territory. They could be held for the duration of the war. We have acquired our own Souvenir de Captivité- a simple wooden piece, almost certainly carefully hand carved by someone with a lot of time. The central aperture would have held a photo.

This one is more difficult to date but also would have held photos of either comrades in arms or loved ones from home.

There's something quite moving about these young men, far from home, spending days making these intricate items for their loved ones out of whatever they had to hand. They are artifacts of an extraordinary emotional investment. Once the men returned home, the meaning changed- they became souvenirs of their time away. Perhaps, like kitsch souvenirs of holidays they were kept on mantelpieces. It is certainly not sophisticated 'art' but for us they are powerful reminders of something that a lot of men went through 100 years ago.

Comments